I found myself in a dingy sixth-floor walkup on Bleecker Street, staring at the front page of The New York Times spread across my desk like a shroud. April 16, 1912. The words swam before me, coalescing into a headline that seemed to pulse with each beat of my heart:

TITANIC SINKS FOUR HOURS AFTER HITTING ICEBERG; 866 RESCUED BY CARPATHIA, PROBABLY 1250 PERISH; NOTED NAMES MISSING

My fingers traced the outline of an iceberg depicted in the hasty illustration. Something cold settled in my stomach, something beyond the cheap whiskey I’d been nursing since dawn. I reached for the bookshelf behind me, fingers finding the worn spine without looking. Futility, my novella published fourteen years earlier. I’d recently seen it retitled in bookshops as The Wreck of the Titan, a transparent attempt by my publisher to capitalize on the publicity of the maiden voyage of the Titanic. The familiar weight of it in my hands felt suddenly alien.

Same month. Same ocean. Same iceberg. Same insufficient lifeboats. Even the names, Titan and Titanic, echoed each other like a voice calling into a canyon.

“Coincidence,” I whispered to the empty room. “Nothing but coincidence.”

Yet the word hung hollow in the air, crowded out by the steady drip of the leaking faucet marking time like a metronome. Drip. Drip. Drip.

Outside my window, Manhattan continued its relentless forward motion. Horse-drawn carriages competed with automobiles. The elevated trains rattled overhead. None of them paused to consider the weight pressing down on my shoulders, the question that had kept me awake for three straight nights.

How had I known?

The next morning, wandering toward Union Square, collar turned up against the spring chill. My feet moved of their own accord, carrying me toward the financial district where the masters of currency made their dominion. I hadn’t intended to go downtown, yet something pulled me toward the epicenter of power like a tide.

“Robertson? Morgan Robertson, is that you?”

I turned to find William Harrington extending his hand, his smile revealing too many teeth. Once a fellow writer of middling talent, he’d traded his pen for a ledger five years ago, taking a position at First National Bank, an institution with direct ties to J.P. Morgan himself.

“William,” I nodded, accepting his handshake. His grip was firmer than I remembered, his suit finer. Success had polished him into something harder than the bohemian I’d once known.

“You’re looking…” he paused, taking in my frayed cuffs, the ink stains on my fingers, “…artistic as ever.”

“And you’re looking prosperous,” I replied. “Banking suits you.”

“It puts food on the table,” he said with practiced humility that didn’t reach his eyes. “More reliable than chasing muses.”

We fell into step together, an old habit from when we’d both frequented the same literary salons. Now we moved through different worlds.

“Terrible business with the Titanic,” he said after a pause. “I suppose you’ve been following it closely.”

“As has everyone.”

“Mmm.” He adjusted his gold cufflinks, new money on display. “Life imitating art in your case, wouldn’t you say?”

My steps faltered. “I beg your pardon?”

“Your book. The Wreck of the Titan. Rather prophetic, wasn’t it?” His tone was light, conversational, but something in his eyes made my skin prickle. “Fiction becoming reality. It’s almost as if…” he trailed off, then chuckled. “Well, some coincidences strain credulity, don’t they?”

“It’s just a story,” I said, more defensively than I’d intended.

“Of course.” William clapped me on the shoulder. “Just a story. Though between us, Morgan, some of the gentlemen at the bank found it quite… inspiring.” He checked his pocket watch. “I must be going. Lunch sometime? For old times’ sake?”

He was gone before I could respond, swallowed by the crowd, leaving me with a chill that had nothing to do with the April air.

That afternoon, I found myself at the offices of Harper’s Weekly, where an editor I knew owed me a favor.

“Passenger lists? What are you working on, Robertson, a memorial piece?” Jenkins shuffled through stacks of telegrams, pulling out several sheets. “Everyone’s writing about the Titanic. Market’s flooded already.”

“Just research,” I mumbled, accepting the papers gratefully.

I sequestered myself in a corner of the bustling office, scanning the lists of the saved and the lost. Most meant nothing to me, names without faces. But three caught my attention. John Jacob Astor IV, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus. Titans of industry, all drowned in the frigid Atlantic.

I took out a notebook, my constant companion, and began jotting down what I knew of each man. Wealthy beyond imagination. Powerful. Connected.

And according to rumors I’d heard in certain literary circles where politics occasionally intruded, all three opposed to the creation of a central banking system in America.

The same central banking system that J.P. Morgan, who had canceled his booking on the Titanic at the last moment, had been advocating for years.

“Coincidence,” I whispered again. But the word had lost all meaning.

I continued my research, moving from the passenger lists to newspaper clippings about banking legislation. By late afternoon, I’d filled ten pages with notes that, taken individually, signified nothing. Collectively, they formed a pattern that made my hands tremble.

Three days later, I received an unexpected invitation to the offices of Avery Publishing, where a young editor named Thomas Caldwell had expressed interest in my work before the Titanic disaster. I arrived to find the reception area crowded with aspiring writers clutching manuscripts like life preservers.

“Mr. Robertson.” Caldwell greeted me with the enthusiasm of youth not yet beaten down by the industry. “Thank you for coming. Please, follow me.”

He led me through a maze of desks to his modest office, closing the door behind us.

“I wanted to discuss your next project,” he said, gesturing for me to sit. “In light of recent events, there’s considerable interest in maritime stories. Your previous work has proven… prescient.”

While he spoke, my eyes were drawn to something on his bookshelf, my novella, Futility, but not the commercial edition. This was a bound typescript, an early version I’d submitted years ago.

“May I?” I asked, standing without waiting for permission. I took the manuscript down, opened it, and felt my heart stutter.

The margins were filled with annotations in red ink. Not editorial notes, but something else, names, dates, calculations. Next to my description of the Titan’s dimensions, someone had written “Adjust by 20% for feasibility.” Beside the passage describing the collision, a note read: “Northern passage ensures maximum casualties w/minimum witnesses.”

Most disturbing of all, next to the character of Rowland: “Use Robertson’s alcoholism against him if necessary.”

“Where did you get this?” I asked, struggling to keep my voice steady.

Caldwell’s expression shifted subtly. “It was here when I took over the office from my predecessor.” His eyes darted to the door. “I really think we should discuss your next book, Mr. Robertson. Perhaps something less… maritime? A western, maybe?”

I closed the manuscript, suddenly aware that this young man was afraid. “Who gave you this office, Thomas?”

He swallowed visibly. “Mr. Avery promoted me after Mr. Harrington left to work in banking.”

William Harrington. My old friend.

“I should go,” I said, tucking the annotated manuscript under my arm.

Caldwell didn’t try to stop me. “Mr. Robertson,” he called as I reached the door. “Be careful what you write next. Some stories aren’t meant to be told.”

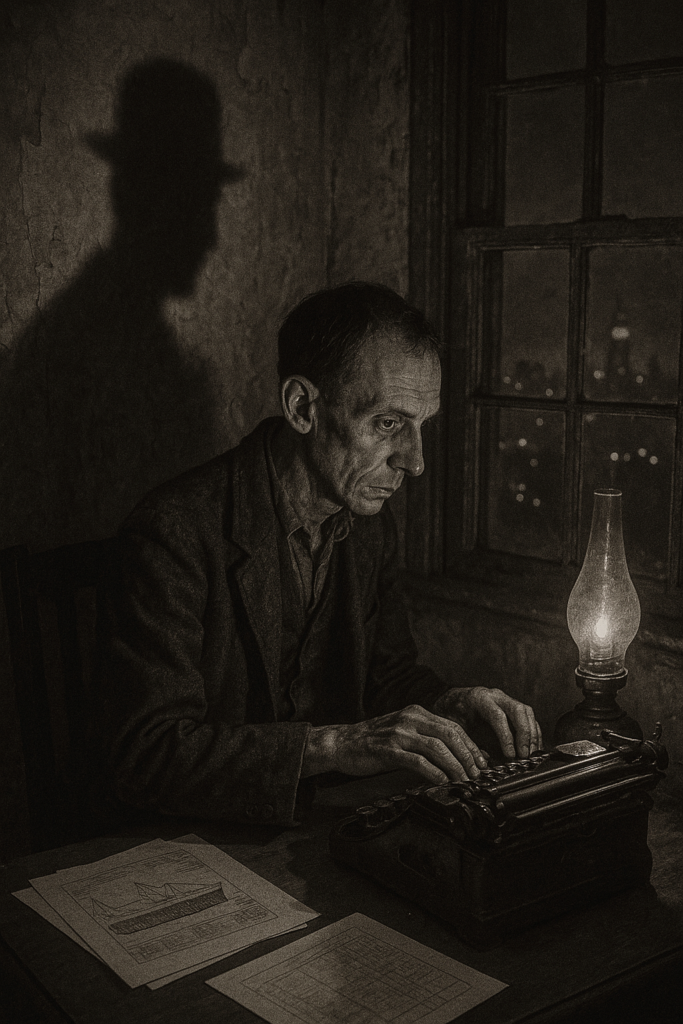

The manuscript lay on my desk that night, its pages illuminated by a single gas lamp casting long shadows across my rented room. Outside, the city rumbled on, unaware of the terrible choice forming in my mind.

I could burn this evidence, dismiss the connections as the desperate pattern-making of a writer’s imagination, and return to my struggling career. Safe. Anonymous. Sane.

Or I could pull at these threads and see what unraveled.

I opened my desk drawer and withdrew a fresh sheet of paper. My hands shook as I inserted it into my typewriter.

The keys clacked into the silence of my room: THE UNSINKABLE TRUTH.

I had made my choice.

Life once again felt real.

I spent the following week in a fever of research, haunting libraries and newspaper archives with the singularity of purpose that had once made me a passable sailor. Sleep became an inconvenience, food an afterthought. The city around me faded into background noise as I assembled my evidence piece by piece.

The New York Public Library became my sanctuary. I claimed a corner desk behind the stacks where I could watch the entrance while remaining half-hidden. Here, surrounded by the musty perfume of aging paper, I traced the insidious connections between shipping magnates and banking interests, between politicians and the quiet men who truly held power.

“You’ve been at it for hours,” whispered the librarian, Ms. Holloway, as she placed a cup of water at my elbow. A small kindness that nearly broke me. “What are you working on that’s so absorbing?”

I glanced up at her, momentarily pulled from my tunnel of concentration. In her eyes, I saw genuine curiosity untainted by suspicion.

“The architecture of shadows,” I replied, instantly regretting the cryptic response. Writers and our precious metaphors. “Financial history,” I amended, offering a more reasonable explanation.

She smiled, a brief illumination in the dim corner. “If you need the financial section records, let me know. We received some new archives from the Treasury Department last month.”

I thanked her, making a mental note to request those records tomorrow. For now, I turned back to the article before me, a seemingly innocent piece about J.P. Morgan’s art collection, but which contained a photograph of Morgan standing alongside several men at a gallery opening. Among them, nearly hidden in the background, was William Harrington. My old friend, now moving in rarefied circles indeed.

As I left the library that evening, the prickling sensation between my shoulder blades returned. Someone was watching me. I’d felt it intermittently since my conversation with William, but tonight it intensified. Without breaking stride, I crossed Fifth Avenue against the traffic, weaving between horse carts and motorcars with practiced recklessness.

Glancing back, I caught sight of a man in a bowler hat who had followed my dangerous crossing. Our eyes met briefly before he turned away, suddenly interested in examining a shop window. Too deliberate. Too obvious.

I doubled back, took two streetcars in opposite directions, and walked the final mile to my apartment. Paranoia, perhaps, but it kept my heart pounding in a rhythm that meant I was still alive.

The lock on my apartment door had been picked. It was a subtle thing, the slight scratches and misalignment of the mechanism that I’d learned to recognize during my less reputable days. I stood in the hallway, key suspended between my fingers, weighing my options.

Whatever they had been looking for, they’d had plenty of time to find it or to wait inside for my return. I chose to enter.

The room appeared untouched at first glance, but I knew better. The disorder was too precise, too methodical. My papers had been examined and replaced with near-perfect attention to detail. Near-perfect, but not quite. The edges didn’t align by a quarter inch. My typewriter ribbon had been advanced slightly. The drawer containing my personal correspondence was closed completely, I always left it open a crack to monitor intrusions.

Most telling of all, the annotated manuscript was exactly where I’d left it. They wanted me to know they’d been here. That they knew what I knew. That they could reach me anywhere.

I sat heavily in my desk chair, suddenly exhausted. The game had escalated before I’d even learned all the rules.

“I have something on the banking legislation you asked about,” said Jenkins when I returned to Harper’s Weekly the next day. His usually animated face was oddly flat, his voice lower than normal.

“What did you find?” I asked, following him to his cluttered desk.

Jenkins glanced around before responding. “Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“That’s right. Nothing.” He slid a blank sheet of paper toward me. “There’s nothing to find, Robertson. Nothing at all.”

I stared at him, uncomprehending, until I saw the edge of fear in his eyes.

“Jenkins, what happened?”

“Two gentlemen visited the editor yesterday,” he said, straightening papers that didn’t need straightening. “Very interested in who’s been researching certain financial matters. Very interested indeed.”

My stomach turned to ice. “And you told them about me.”

“I’m sorry.” He wouldn’t meet my eyes. “They knew anyway. They just wanted confirmation.”

“I understand,” I said, though I didn’t, not really. Self-preservation was a powerful instinct. I couldn’t blame him for it.

“There’s something else.” Jenkins lowered his voice further. “Michaels was fired this morning.”

“The financial editor? Why?”

“Official reason is budget cuts. But it happened right after he gave you those telegrams about the Titanic passengers.” Jenkins finally looked at me directly. “Whatever you’re onto, Robertson, it’s bigger than both of us. Let it go.”

I left Harper’s feeling the weight of unseen eyes tracking my movements. The city I’d known for decades suddenly seemed alien, its familiar contours reshaped by invisible hands. Were the newsboys on the corner really selling papers, or were they watching me? Was the shoe-shine man reporting my movements? How far did this web extend?

That evening, I met James Thornton at his gentleman’s club near Gramercy Park. Thornton was an established journalist with The World who had built his reputation on exposing corruption. If anyone would listen without dismissing me outright, it would be him.

The club was beyond my usual means, all polished mahogany and leather chairs occupied by men who controlled empires from comfortable distance. I felt conspicuous in my shabby suit as the doorman regarded me with poorly concealed disdain.

“He’s with me, Phillips,” said Thornton, materializing at my elbow. In his tailored evening wear, he looked every inch a member of the establishment he so often criticized.

“You’re looking ragged, Morgan,” he said once we were seated in a quiet corner, brandy glasses between us. “When did you last sleep?”

“Sleep is a luxury,” I replied, then caught myself. I needed to sound reasonable, measured. Paranoid ramblings would get me nowhere. “I’ve been working on something important.”

For the next twenty minutes, I laid out my findings as methodically as possible. The connections between the Titanic victims and their opposition to central banking. The timing of Morgan’s canceled passage. The annotated manuscript with its disturbing marginalia. The pattern of surveillance and intrusion that had followed my investigation.

Thornton listened without interruption, occasionally sipping his brandy. When I finished, the silence stretched between us, punctuated by distant conversations and the clink of glasses.

“That’s quite a tale,” he said finally.

“It’s not a tale,” I insisted. “It’s a conspiracy of monumental proportions.”

Thornton set down his glass and leaned forward. I prepared myself for his journalistic instincts to kick in, for the questions that would help sharpen my investigation.

Instead, he laughed.

It wasn’t cruel laughter, which somehow made it worse. It was the indulgent chuckle one reserves for a child with an overactive imagination.

“Morgan,” he said, with the gentle condescension of a doctor addressing a patient, “you’re a writer. A good one. But you’re seeing plots where there’s only chaos and coincidence.”

“I have evidence—”

“You have connections that could mean anything or nothing.” He tapped his temple. “The human mind is designed to find patterns, even when they don’t exist. It’s what makes you a talented novelist and what’s leading you down this rabbit hole.”

“The manuscript—”

“Editorial notes, misinterpreted through the lens of your current fixation.” Thornton sighed, genuine concern crossing his features. “When did you start drinking again, Morgan?”

The question struck like a physical blow. “This has nothing to do with drinking.”

“Doesn’t it? Paranoia. Conspiracy theories. Seeing meaning in coincidences. These are the hallmarks of a mind altered by alcohol or…” he hesitated, “or struggling with more serious disturbances.”

“You think I’m insane.” The words felt hollow in my mouth.

“I think you’re exhausted, possibly self-medicating, and have let your writer’s imagination carry you away.” Thornton signaled for another round. “Let this go before you damage what’s left of your reputation.”

I sat in stunned silence as doubts crept in like fog off the Hudson. Was I connecting dots that weren’t meant to be connected? Had I fabricated an elaborate conspiracy from random events and coincidences? The weight of uncertainty pressed down, heavier than any censure.

Thornton drove the final nail with kindness: “Get some rest, old friend. Write fiction where these talents of yours are appreciated.”

I left the club shortly after, Thornton’s patronizing encouragement echoing in my ears. Outside, rain had started falling, transforming gas-lit streets into mirror worlds where everything familiar became distorted.

Maybe I was chasing shadows. Maybe the drinking had affected my mind more deeply than I realized. Maybe…

A familiar figure caught my eye across the street. William Harrington, emerging from the same club I’d just left, clasping Thornton on the shoulder with the easy familiarity of old friends.

The cold certainty returned, washing away doubt. I wasn’t insane. I wasn’t imagining the connections.

I just couldn’t trust anyone to believe them.

Back in my apartment, I found an envelope that had been slipped under my door. Inside, a notice from my bank stating that my account had been closed due to “irregular activities.” My meager savings, gone.

On my desk sat a letter from Avery Publishing, rejecting the partial manuscript I’d submitted the previous month, though they had expressed enthusiasm for it just weeks earlier. The rejection was accompanied by a terse note suggesting that my “recent preoccupations” had affected the quality of my work.

One by one, my professional connections were dissolving. My financial resources had evaporated. My credibility was being systematically undermined.

I slumped onto my bed, the mattress springs protesting beneath me. The room spun slightly, fatigue and hunger taking their toll. How does one fight an enemy that exists in the shadows? How does one expose a truth that no one wants to hear?

Through my window, I could see the lights of Manhattan, each one representing lives untouched by the knowledge that consumed me. How many transactions would occur tomorrow, each one feeding the invisible parasite I’d glimpsed? How many people would unknowingly surrender a portion of their productivity to the creature that lurked just beyond perception?

I closed my eyes, just for a moment. Just to think.

The dripping faucet marked time with relentless precision.

Drip.

Drip.

Drip.

Like coins falling into an endless void.

I awoke to insistent knocking, my neck stiff from falling asleep at my desk. Morning light filtered through grimy windows, revealing dust motes dancing in the air. The knocking continued, more urgent now.

“Coming,” I called, voice rough with sleep.

No response, just the steady rap of knuckles against wood. I approached cautiously, checking the baseball bat I kept beside the door, a relic from more optimistic days when leisure seemed possible.

No one stood in the hallway. Instead, a small package wrapped in brown paper rested on the threshold. No markings, no address, no indication of its sender. I scanned the empty corridor before retrieving it, half-expecting an ambush that never came.

Back inside, I examined the package with the wariness of a man who suddenly finds himself in possession of a venomous snake. It was light, about the size of a book. After a moment’s hesitation, I unwrapped it.

Inside lay a folder containing what appeared to be private correspondences, letters, telegrams, and memoranda on bank letterhead. My hands trembled as I spread them across my desk. Here was evidence I couldn’t have fabricated or imagined.

One telegram, dated April 2, 1912, ten days before the Titanic’s departure, read:

ARRANGEMENTS CONFIRMED STOP ALL TARGETS BOOKED FOR CROSSING STOP ENSURE VESSEL ROUTE COORDINATES AS DISCUSSED PREVIOUS MEETING STOP

A letter from one banking executive to another, dated April 18, two days after the sinking:

My dear Phillips,

The regrettable loss of the vessel has indeed resulted in the fortunate removal of obstacles to our endeavor. With Astor, Guggenheim, and Straus no longer positioned to influence congressional opinion, we anticipate smooth passage of the legislation by year’s end. The sacrifice, while lamentable in humanitarian terms, will ultimately benefit the greater economic stability of our nation.

I trust you will burn this letter upon reading.

Yours in confidence, W.H.

W.H. William Harrington.

Most damning of all was a memorandum outlining the benefits of a centralized banking system, with a handwritten note in the margin:

Robertson’s fiction provides perfect cover, tragic prescience rather than deliberate action. Monitor him for signs of connection.

My head spun as I processed the implications. Not paranoia, not delusion, truth. A terrible truth that transformed my novella from an innocent work of imagination into an unwitting blueprint for mass murder.

I spread the documents before me, arranging them in chronological order. Together, they revealed an orchestrated plan spanning years, not merely to eliminate specific opponents but to reshape America’s financial system. The sinking of the Titanic wasn’t just a tragic accident or even a targeted assassination, it was a ritualistic sacrifice to birth a new economic order.

And I had provided the template.

The question of who sent these documents plagued me as I spent the day verifying their authenticity. The letterhead matched known financial institutions. The signatures, when compared to published examples, appeared genuine. The paper stock was expensive, the kind used in executive offices rather than public correspondence.

Someone on the inside had broken ranks. Someone with access and, perhaps, with conscience.

As sunset turned my windows to sheets of amber, a theory formed. Thomas Caldwell, the young editor who had shown me the annotated manuscript, who had warned me to be careful. He had inherited Harrington’s office, would have access to his files. Perhaps in the process of settling in, he had discovered something that disturbed him deeply.

I needed to speak with him urgently.

The Avery Publishing offices were closed by the time I arrived, but a light burned in a third-floor window. The night watchman, familiar with my occasional late visits during better days, allowed me inside with nothing more than a cursory greeting.

I climbed the stairs silently, suddenly aware of how exposed I was. If Caldwell wasn’t my ally, I was walking directly into danger. And yet, I had to know.

The corridor was dark save for a slice of light escaping from beneath Caldwell’s door. I knocked softly.

“Come in,” called a voice that wasn’t Caldwell’s.

I hesitated, hand on the doorknob, instinct screaming for retreat. But curiosity, that writer’s curse, pushed me forward.

William Harrington sat behind Caldwell’s desk, a glass of whiskey in his manicured hand, looking for all the world like he belonged there.

“Morgan,” he smiled, raising his glass in greeting. “I was hoping you’d come. Please, join me.”

I remained in the doorway, scanning the room for Caldwell. “Where is Thomas?”

“Called away on family business,” Harrington replied smoothly. “Tragic situation with his mother’s health. The firm has granted him extended leave.”

The lie was as polished as Harrington himself. I wondered if Caldwell was alive at all.

“What did you do to him?”

Harrington’s smile faltered slightly. “Always the dramatist. Sit, Morgan. We have much to discuss.”

Against my better judgment, I entered, leaving the door open behind me. “I’d prefer to stand.”

“As you wish.” Harrington sipped his whiskey, studying me over the rim of his glass. “You’ve been busy lately. Libraries, newspapers, banks. Asking questions about matters that don’t concern you.”

“Mass murder concerns every man with conscience.”

“Ah, conscience.” He savored the word like a foreign delicacy. “That persistent voice whispering in our ears, constraining our potential. Tell me, Morgan, has your conscience served you well? Has it put food on your table or respect in men’s eyes?”

“It’s kept me human.”

Harrington laughed, a sound like leather stretching. “Humanity is overrated. Evolution demands transcendence.”

“Is that how you justify killing hundreds of innocent people? Evolution?”

“Collateral damage in service of progress.” He waved his hand dismissively. “The central banking system will stabilize the economy, prevent the kind of panics that nearly collapsed our financial system in ’07. The few who die today save the many who would starve tomorrow.”

“Noble sentiments from a man who made sure he wasn’t on the ship.”

Something dangerous flashed across Harrington’s face, a momentary glimpse behind the mask. Then it was gone, replaced by practiced charm.

“I received your package,” I said, watching him carefully.

Confusion flickered in his eyes. “What package?”

A genuine reaction. The documents hadn’t come from him, hadn’t been a trap. Interesting.

“Evidence,” I replied vaguely. “Names, dates, plans. Enough to expose everything.”

Harrington’s posture shifted subtly, the predator recalculating. “I highly doubt that. But let’s assume you have something worth considering. What do you intend to do with it?”

“What any writer would do. Tell the story.”

“And who would publish such a tale? You’ve already discovered how quickly doors close.” He leaned forward. “But they could open again, Morgan. Your talents are recognized in certain circles. Your… predictive abilities have proven valuable. There could be a place for you.”

“With you? With the people who twisted my work into a murder plot?”

“With the architects of tomorrow.” Harrington stood, moving to the window overlooking the city. “Look at them down there, scurrying about, living hand-to-mouth, paycheck to paycheck. They’re trapped in a system they don’t understand, giving away their productivity piece by piece.”

He turned to me, eyes alight with fervor I’d never seen during his writing days. “We’re creating something new, Morgan. Something living. A financial organism that transcends individual banks or businesses. It flows through every transaction, takes its percentage, grows in the darkness.”

The hairs on my neck rose at hearing my own thoughts about the parasitic nature of the system echoed back to me. But where I saw horror, Harrington saw glory.

“You could help shape it,” he continued. “Your imagination, your ability to foresee consequences, these are rare gifts. Join us. Comfort. Recognition. Legacy. All can be yours.”

For a moment, one shameful moment, I considered it. The years of struggle, of rejection, of watching inferior writers achieve the success that eluded me. The nights wondering if I’d ever make a mark on the world.

Then I thought of the ice-cold water closing over hundreds of heads. Of children crying for parents they’d never see again. Of Astor, Guggenheim, and Straus, murdered for opposing a banking scheme.

“I’d rather drown,” I said finally.

Harrington sighed, returning to his seat. “I anticipated that response. Unfortunate, but not unexpected.”

He opened a drawer and withdrew a folded newspaper. “This is tomorrow’s early edition. I thought you might find the headline interesting.”

He slid it across the desk. The front page featured my photograph alongside the headline: NOVELIST SUFFERS BREAKDOWN, CLAIMS TITANIC DISASTER CONSPIRACY.

My blood ran cold. “This hasn’t happened.”

“But it will,” Harrington replied smoothly. “Tonight, in fact. After several witnesses observe you ranting about banking conspiracies and Titanic murders at the Whitehall Club. After you physically assault a respected journalist who attempts to calm you. After you’re escorted from the premises, clearly intoxicated and delusional.”

“I’ve been in my apartment all day. I haven’t been to any club.”

“Five prominent members of New York society will testify otherwise.” Harrington checked his pocket watch. “In approximately one hour, I believe.”

I stared at the paper, understanding dawning. “You’re framing me.”

“Discrediting you,” he corrected. “There’s a difference. No prison time, just the complete annihilation of your credibility. Though I expect The Retreat on Long Island might extend an invitation for an extended stay in their psychiatric facilities.”

The walls seemed to close in around me. They’d thought of everything. Even if I published my findings, who would believe the ravings of a man publicly declared insane?

“You won’t get away with this,” I said, the words sounding hollow even to my own ears.

“We already have.” Harrington stood again, straightening his cuffs. “Now, I have a gathering to attend at the Whitehall Club, where your public breakdown is scheduled to occur. I would invite you along, but…” he smiled thinly, “your presence would complicate matters.”

He moved toward the door, then paused. “A word of advice, Morgan. The evidence you claim to possess? Destroy it. Move on. Write your little stories. Perhaps we’ll even arrange for modest success, enough to live comfortably, not enough to gain significant influence. A man of your imagination could have years of productive creativity ahead.”

As he reached the doorway, he turned back. “Or not. The choice, as always, is yours.”

Then he was gone, footsteps echoing down the corridor.

I stood alone in Caldwell’s office, holding a newspaper reporting events that hadn’t yet happened. My ruination, scheduled like a theater performance. My future, determined by men who treated human lives as entries in a ledger.

I sank into Caldwell’s chair, the weight of my situation crushing down upon me. They controlled the newspapers, the banks, the publishers. They could create reality as easily as I created fiction.

What chance did a single, discredited author have against such power?

Outside the window, New York’s lights twinkled innocently, unaware of the darkness gathering at its financial heart. Somewhere in that glittering landscape, men in evening wear were preparing to testify to my madness. Somewhere, the machinery of my destruction was already in motion.

I had never felt more alone.

Or more certain that I had uncovered a truth that was never meant to be found.

I remained in Caldwell’s office long after Harrington’s departure, the falsified newspaper still clutched in my trembling hands. Outside, night had fully claimed the city. Gas lamps cast halos in the fog that rolled in from the harbor, the same harbor where, months earlier, the Carpathia had delivered 705 souls who had glimpsed mortality on the Atlantic.

What would I have written, had I known my novella would become a blueprint for murder? Would I have left Rowland’s character to drown instead of saving him? Would I have made the Titan unsinkable in truth rather than hubris? Or would I have set the story on land, far from icebergs and the cold equations of maritime disaster?

The questions circled like vultures as I stared at my own face on the front page of tomorrow’s news. The photograph they’d selected was from better days, before the drinking, before the failures, when my eyes still held the confidence of a man who believed words could change the world.

Perhaps they could.

I folded the newspaper and placed it in my jacket pocket. Evidence, though no court would ever see it. Then I did something that would have been unthinkable hours before, I returned to Harrington’s desk and began methodically searching it.

If he had orchestrated my destruction so thoroughly, perhaps I could find something to orchestrate his.

The drawers yielded little at first, standard publishing contracts, correspondence about manuscripts, editorial notes. But behind the bottom drawer, taped to the underside of the desk, I found a small key.

It fit a locked cabinet in the corner of the room, which opened to reveal a leather-bound ledger. Inside were names, dates, and numbers, transactions of some kind, but not publishing-related. The sums were too large, the notation too cryptic. Interspersed with the figures were symbols I didn’t recognize, triangles with eyes, strange geometric patterns, codes that might have been initials or might have been something else entirely.

On the final page, a list of names. Some crossed out, Astor, Guggenheim, Straus. Others unmarked, including congressmen, judges, journalists. At the bottom, added recently in the same elegant script that had annotated my manuscript: Morgan Robertson, monitor and neutralize if necessary.

I had been right, but the truth was far worse than even my imagination had conceived. This wasn’t merely about eliminating opposition to a central bank. This was about control, systematic, generational control of the mechanisms that governed society.

I slipped the ledger into my coat, alongside the newspaper. Then, moving with purpose I hadn’t felt in years, I crossed to Caldwell’s typewriter and inserted a sheet of paper.

If they could create false narratives, so could I. But mine would be seeded with truth.

Dawn found me still writing, ribbon running low on ink, fingers cramped from hours of typing. I had produced nearly forty pages, not a work of fiction, but a detailed account of everything I had discovered. The connections between the banking interests and the Titanic disaster. The annotated manuscript. Harrington’s confession. The falsified news account prepared before events it claimed to report.

Most importantly, I included my own role in the tragedy, how my imagination had provided the framework for their scheme. My sin wasn’t in plotting murder, but in creating fiction so compelling it could be weaponized by those without conscience.

I titled it simply: The Unsinkable Truth: A Confession and Warning.

As I typed the final words, exhaustion washed over me. I hadn’t slept properly in days. Hadn’t eaten. Had barely remembered to drink water. My body was failing even as my mind achieved perfect clarity.

I gathered my pages, the ledger, and the falsified newspaper, securing them in a large envelope. Then I made my way to the one person I believed might still be untouched by the conspiracy’s reach, Ms. Holloway at the library.

She greeted me with concern written across her features. “Mr. Robertson, you look terrible.”

“I feel magnificent,” I replied, and meant it. “I need a favor.”

I handed her the envelope. “Keep this safe. Don’t open it yet. If anything happens to me, anything strange or sudden, I want you to deliver copies to every newspaper in the city. Can you do that?”

She took the envelope hesitantly. “Are you in some kind of trouble?”

“I’ve stumbled into a great darkness,” I said, “and found it staring back.”

“Perhaps you should speak with someone. A doctor, maybe?”

“Everyone says that.” I smiled wearily. “Promise me you’ll do as I ask.”

She nodded, though uncertainty clouded her eyes. “I promise.”

I thanked her and turned to leave, but her voice stopped me at the door.

“Mr. Robertson? Whatever it is you’re involved in… be careful.”

I nodded, knowing that careful was a luxury I could no longer afford.

My apartment felt different when I returned, not violated as before, but waiting. As if the space itself had become conscious of impending conclusion.

I washed my face in the rust-stained sink, catching my reflection in the cracked mirror above it. I hardly recognized the man staring back, eyes sunken, cheeks hollow, skin sallow from too many hours indoors. But there was something new there too, a fierce light that hadn’t been present in years. Purpose.

The dripping faucet kept its steady rhythm. Drip. Drip. Drip.

I had one task remaining. I needed to write the final chapter, not of my exposé, but of my understanding. The piece that had eluded me until now, the true nature of what Harrington had described as “something living.”

I sat at my desk, inserted a fresh sheet into my typewriter, and began:

THE PARASITE

It has no body we can see. No physical form we can touch. But it lives nonetheless, growing fat on human productivity, on the silent percentage it extracts from every transaction.

I once believed that men like Morgan and Harrington were the architects of this system. I was wrong. They are merely its custodians, its high priests. The system itself transcends them, existing beyond human lifespan, adapting across centuries.

It began with the goldsmiths and their receipts. Simple paper representing gold stored safely in their vaults. Then the revelation that they could issue more receipts than gold they possessed, as long as not everyone claimed their metal at once. Money from nothing. Wealth from mere confidence.

With each evolution, banks, stock markets, central banking systems, it has grown more abstract, further removed from physical reality, harder to perceive. The percentage it takes has become invisible, automatic, assumed.

What we call an economy is, in truth, a parasite so completely bonded with its host that we mistake it for ourselves.

I have glimpsed this creature. I have felt its cold attention turn toward me. And I understand now that no single person, no matter how powerful, truly controls it. They serve it, feed it, protect it, and in return, it grants them privilege and power.

The Titanic was not merely a tragic accident. Not merely a targeted murder. It was a sacrifice to this entity, a demonstration of its reach and a warning to those who would oppose its growth.

My novella provided cover, plausible deniability through prediction. “How could it be conspiracy when it was written years before?” The perfect shield against accusation.

I do not expect to survive this understanding. The creature has seen me seeing it, and that cannot be permitted. But perhaps, someday, someone else will glimpse its outline. Someone who can do what I cannot… kill it before it consumes us all.

I finished typing as evening shadows stretched across my room. Outside, footsteps paused at my door. A gentle knock followed.

“Come in,” I called, knowing who it would be.

Dr. Martin entered, medical bag in hand, concerned smile on his lips. An old friend. One of the few who had stood by me through the drinking years.

“Morgan,” he said warmly. “William asked me to check on you. Said you’ve been working too hard, not sleeping.”

Of course. Harrington would send someone I trusted. Someone whose presence wouldn’t alarm me.

“How thoughtful of him,” I replied, offering the chair opposite mine. “I’ve been better, I admit.”

“So I see.” Martin set his bag on the table, eyes clinical now, assessing. “You’re not drinking again, are you?”

“Not a drop in months.”

“Good, good.” He nodded, removing a stethoscope. “Mind if I take a listen? William mentioned palpitations.”

I complied, unbuttoning my shirt as Martin pressed the cold metal to my chest. His frown deepened as he listened.

“Your heart’s racing,” he said. “And you’re clearly malnourished. When did you last eat?”

“I can’t recall.”

He clucked his tongue disapprovingly. “I’m going to give you something to help you rest. Then tomorrow, we’ll discuss a proper recovery regimen.”

From his bag, he withdrew a small bottle, amber glass with a simple label. Paraldehyde.

“Just a small dose,” he assured me, pouring the liquid into a glass, adding water from the pitcher on my desk. “To help you sleep.”

I watched him prepare the mixture, feeling a strange calm settle over me. So this was how it would happen. Not violence. Not confrontation. Just a quiet overdose administered by a concerned physician who was either complicit or deceived.

“Tell me, James,” I said as he handed me the glass, “how long have you known William?”

“Harrington? Years now. Fine fellow. Concerned about you.”

“And have you done this before? For him?”

Martin’s eyes flickered, just momentarily, before his professional mask returned. “Done what, Morgan? Treated a friend suffering from exhaustion?”

That slight hesitation told me everything. He knew. Maybe not all of it, but enough.

“Of course,” I smiled, raising the glass in toast. “To good friends, then.”

Martin visibly relaxed. “To your health.”

I brought the glass to my lips but didn’t drink. “One last question.”

“Yes?”

“When I die tonight, because we both know that’s what this is, will you list the cause as heart failure?”

The silence between us stretched taut. Then, softly, “It would be kinder to your memory than the alternative.”

“The alternative being?”

“That you took your own life. Paraldehyde overdose, commonly used by those suffering from delirium tremens. A troubled alcoholic unable to escape his demons.”

I nodded slowly. “The story writes itself.”

“It will be painless, Morgan,” he offered, as if that were a consolation. “You’ll simply fall asleep.”

I studied him, this man I had once called friend, now Death’s polite ambassador. “And my papers? My typewriter?”

“I’m to bring anything you’ve been working on to William. For safekeeping.”

“Of course.” I gestured to the neatly stacked pages beside my typewriter. “My final work. Make sure it reaches him.”

Martin nodded, relief evident in his posture. He thought I was accepting my fate. Perhaps I was.

I raised the glass again and this time took a sip. The bitter taste of paraldehyde filled my mouth, but I didn’t swallow. Instead, I held it there, nodding as if appreciating a fine wine.

“Try to drink it all,” Martin urged gently. “It works best that way.”

I stood suddenly, moved to the window, and spat the liquid outside. “I’m afraid I can’t oblige you tonight, James.”

His face hardened. “Don’t make this difficult, Morgan. It’s happening either way.”

“I know.” I set the glass down. “But not just yet.”

I returned to my desk, sat down, and inserted a fresh sheet of paper into my typewriter. “I have one last scene to write.”

“Morgan—”

“Sit, James. Please.” I gestured to the chair. “You can wait. I won’t take long.”

Perhaps it was curiosity, or perhaps some lingering respect for a dying man’s wishes, but Martin sat.

I began typing, the keys striking with definitive purpose.

In my final hours, I am visited by Dr. James Martin, bearing paraldehyde, the same substance used to sedate alcoholics suffering withdrawal. He comes at William Harrington’s behest, with instructions to collect my papers after my death and attribute my passing to heart failure rather than poisoning.

Martin shifted uncomfortably. “What are you writing?”

I continued without answering.

I do not blame James entirely. He is merely another appendage of the creature I have described, another vessel through which it flows and acts. He believes he is helping a friend avoid scandal in death, protecting a reputation already in tatters.

What he doesn’t yet understand is that I anticipated this visit. That copies of everything I’ve discovered, including this final testament, have already been secured with instructions for their distribution should anything happen to me.

This was a lie, of course. Ms. Holloway had only one copy, and I doubted she would follow through once news of my “breakdown” spread. But Martin didn’t know that.

“Morgan, stop this nonsense,” he said, standing now, agitation evident in his movements. “You’re only making things worse.”

The physician grows nervous as I commit his role to paper. Perhaps, for the first time, he glimpses how history might view his actions tonight. Not as mercy, but as murder. Not as kindness, but as conspiracy.

Martin crossed to me in two swift strides, reaching for the typewriter. I raised my hand to block him.

“Sit down, James. Let me finish.”

“I can’t let you do this.”

“You can’t stop it either. The words are already written, the mechanism already in motion.” I met his gaze steadily. “Sit. Down.”

Something in my voice, the absolute certainty, perhaps, made him comply.

I returned to typing.

I will drink the paraldehyde shortly. Not because I fear what comes otherwise, but because I have accomplished what I needed to. I have seen the parasite. I have named it. I have exposed its mechanisms and its servants.

I do not expect to be believed immediately. The creature has had centuries to embed itself in human consciousness, to make itself appear natural and necessary. But seeds, once planted, eventually grow. Truth, once glimpsed, cannot be entirely forgotten.

To those who find these words: Look to the transactions. Look to the percentages. Look to the invisible taxations that occur with each exchange of value. See how they flow upward, always upward, to unseen reservoirs of power.

The Titanic was just one sacrifice. There will be others. Wars. Depressions. Crises manufactured to feed the creature and justify its expansion.

I go now to my rest, another victim of its hunger. But I do so with the satisfaction of knowing I have wounded it, however slightly. I have seen it. And in seeing, have made it visible to others.

The unsinkable truth remains. We are not free until we recognize our chains.

I pulled the paper from the typewriter with a flourish and added it to the stack. “There. It’s done.”

Martin looked ashen. “You’ve lost your mind.”

“On the contrary,” I smiled, “I’ve found it.”

I picked up the glass of paraldehyde and raised it once more. “To the creature, James. May it choke on its own appetite.”

Then I drank, feeling the bitter liquid burn down my throat. Martin watched, relief and horror mingling in his expression.

“How long?” I asked as warmth began spreading through my limbs.

“Twenty minutes, perhaps.” He wouldn’t meet my eyes now. “You’ll grow drowsy first.”

I nodded, leaning back in my chair. Already the edges of my vision were softening, the room taking on a dreamlike quality.

“Will you do something for me, James? A small kindness for old times’ sake?”

He hesitated, then nodded reluctantly.

“Leave my papers. Just for tonight. Collect them tomorrow if you must, but let them exist in the world for a few more hours.”

“I can’t. William was explicit—”

“What difference will a few hours make? I’ll be dead. The damage contained.”

He considered this, conflict evident in his features. Finally, he said, “Very well. Until morning.”

“Thank you.” I closed my eyes briefly, feeling myself drifting. When I opened them again, the room seemed to pulse with each beat of my heart. “You know what the strangest part is, James?”

“What’s that?” His voice seemed to come from very far away.

“I’m not afraid. I thought I would be, but I’m not.”

“The medication is working.”

“No,” I shook my head, the motion leaving trails of light across my vision. “It’s something else. I’ve seen behind the curtain. I know how the trick works now.”

Martin stood, collecting his bag. “I should go.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “This isn’t a scene anyone should witness.”

He paused at the door, looking back at me. For a moment, I thought I glimpsed regret in his expression. Then he was gone.

I sat alone in my room as the paraldehyde worked its way through my system. The dripping faucet kept time with my slowing heartbeat. Drip. Drip. Drip.

Outside my window, New York continued its ceaseless motion, unaware of the parasite that fed on its productivity, unaware of the man dying in a sixth-floor walkup on Bleecker Street. The city lights blurred into constellations, each one representing a life connected to all others by invisible threads of commerce and exchange.

I wondered if anyone would find my writings before Harrington’s people collected them. I wondered if anyone would believe them if they did.

In my increasingly disjointed thoughts, I imagined my words taking physical form, slipping out through cracks in the floorboards, seeping into the city’s foundation, waiting to be discovered by someone with eyes to see and courage to speak.

The room tilted sideways as I slid from my chair onto the floor. No pain, just a profound heaviness. The ceiling spun above me, patterns forming and dissolving.

In my final moments of consciousness, a strange clarity descended. I saw the parasite fully, not as metaphor but as reality, a vast, patient entity that had evolved alongside humanity, feeding on our transaction points, growing as we grew. Not evil, exactly, but hungry. Always hungry.

And for the first time, I understood that seeing it was the first step toward freedom from it.

My papers rustled gently in the breeze from the window. Whether they would survive until morning, I couldn’t know. Whether my words would reach others who glimpsed the creature, I couldn’t predict.

But I had written the truth as I had seen it. I had completed my final story.

In that achievement, there was a peace I hadn’t known in years.

The dripping slowed. Drip… Drip…

Darkness gathered at the edges of my vision, not threatening but welcoming. The room receded as I sank deeper into the floor, through the building’s foundations, into the bedrock of Manhattan Island.

My last thought was of icebergs, how little shows above the surface, how much remains hidden below.

Then nothing but silence as the unsinkable truth drifted into darkness.