I’m writing this shirtless and sweating in Mexico, window open as the Florida thatch palm rustles in a slight passing breeze. A month and a half shy of my ten-year anniversary of walking away from society, 07/20/15, a date tattooed on my right leg as a reminder to keep walking. A decade of living out of my backpack on America’s National Scenic Trails, and only now am I starting to understand what it was all about.

What it might lead to.

For nearly a decade, I’ve lived inside a functioning democracy that most people never notice. Not the voting-booth democracy that dominates headlines, but the trail democracy that keeps two thousand miles of Appalachian Trail working without central authority.

No single organization controls how your hike unfolds. The National Park Service manages some sections, state agencies handle others, volunteer trail clubs maintain most of the actual infrastructure. Yet the system works seamlessly because information flows freely through overlapping networks of trail registers, shelter logbooks, Facebook groups, and FarOut app comments about water sources and trail magic.

Resources emerge organically from community engagement in shared challenges. Someone posts about a bridge washout, and within hours alternate routes appear in comments. A hiker mentions running low on supplies, and trail magic materializes at the next road crossing. The system responds to hikers’ needs with personalized solutions.

Despite weather challenges, physical exhaustion, mental breakdowns, and financial crises, guidance appears when you need it most. Sometimes impersonally through app notifications, sometimes intimately through handwritten notes in shelter registers. The infrastructure serves individual journeys while building collective knowledge.

Lying in my sleeping bag under the stars, cowboy camping in places that don’t appear on maps, I’ve spent countless nights wondering why the rest of the world doesn’t run this way.

The Technical Answer

(You Can Skip This Section if the How-To isn’t Your Cup of Tea)

The problem isn’t technically complex. Building a prototype social media democracy platform requires only using existing open-source tools arranged in familiar patterns. Think, Facebook meets Wikipedia, owned by nobody, operated as a public utility.

Start with MediaWiki’s content management system, proven at Wikipedia scale for collaborative knowledge creation. Add social features from platforms like Mastodon or Diaspora, federated networks that resist centralized control. Layer in transparent recommendation algorithms from projects like algorithmic auditing frameworks already being developed by academic researchers.

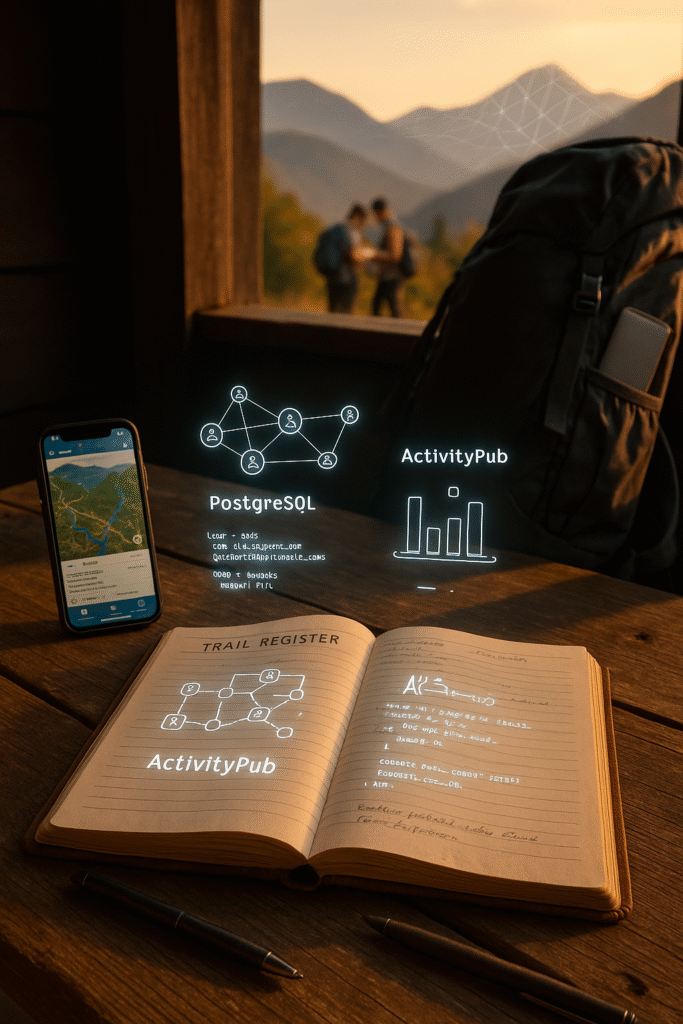

The technical stack practically builds itself:

Backend: Node.js or Python Django for rapid development, PostgreSQL for data integrity, Redis for caching. Standard web infrastructure that any competent developer team could implement.

Frontend: React or Vue.js for responsive user interface, incorporating accessibility standards from the start. Nothing revolutionary, just social media interface design focused on information utility rather than engagement addiction.

Federation: ActivityPub protocol for distributed networking, allowing local communities to maintain their own instances while sharing information across the network. Mastodon already proves this works at scale.

Algorithm Transparency: Open-source content ranking based on relevance and expertise rather than engagement metrics. Users can examine exactly why they’re seeing specific content, modify their own algorithmic preferences, even fork the code to create alternative ranking systems.

Democratic Governance: Community-driven moderation using systems like those already working in Wikipedia, Stack Overflow, and Reddit’s better subreddits. Distributed decision-making, transparent policies, appeals processes that actually function.

The prototype could be built by a small team in six months. Basic social features, transparent algorithms, federated networking, democratic governance structures. Nothing that hasn’t been solved before, just combined with different priorities.

Why Doesn’t This Exist?

That’s the question that keeps me awake in desert campsites and mountain shelters. The technical solution is straightforward. The social need is obvious. Open-source tools exist for every component. Academic research supports the theoretical framework. Trail communities demonstrate it works in practice.

So why am I writing this from a writing retreat in Mexico instead of contributing code to an existing project?

Because building the technology is the easy part. The hard part is convincing people that social media could serve collective intelligence rather than corporate profit. That democracy could emerge from human experience rather than manufactured consent. That individual voices could contribute to policy decisions without being exploited by algorithmic manipulation.

The trail works because everyone who uses it understands the basic principle, individual success depends on collective knowledge. You help others because you need others to help you. The system serves mutual aid rather than competitive advantage.

Translating that principle to digital democracy requires cultural shift as much as technical development. People need to believe that their authentic experience matters more than their performative content. That contributing to collective knowledge serves their individual interests better than optimizing for algorithmic attention.

Is it Possible?

Building the minimum viable platform requires more social architecture than technical architecture. Imagine launching with healthcare workers frustrated by policy decisions made by people who’ve never worked an emergency room shift. They create the first community instance, sharing their front line experiences about resource needs, staffing challenges, patient care realities.

The platform’s transparent algorithm learns to weight insights based on professional experience and relevance rather than engagement metrics. A nurse’s observation about supply shortages carries more influence on healthcare resource allocation than a pharmaceutical lobbyist’s talking points. Within months, policy recommendations emerging from the platform begin reflecting ground-level medical reality instead of boardroom abstractions.

Success attracts educators creating their own federated instance, connecting to the healthcare community while maintaining specialized focus on classroom realities. Teachers document funding needs, curriculum challenges, student support gaps. Their collective insights start informing education policy decisions with unprecedented authenticity.

Geographic communities follow, municipal instances where residents share experiences about local infrastructure, housing costs, and transportation needs. The federated network allows cross-pollination of insights while maintaining focused expertise. A teacher in rural Montana learns from healthcare workers in urban Detroit, both contributing to national policy discussions with voices rooted in lived experience.

Eventually, policymakers discover they can access collective intelligence that traditional polling completely misses. Instead of operating from manufactured constituencies and limited information, they can tap into aggregated wisdom from people actually navigating the systems they’re trying to improve.

The FarOut app already demonstrates this working at trail scale, a hiker’s shared experience as a comment driving content, practical utility over engagement addiction. Scaling that model to broader social issues isn’t technically challenging, it’s politically challenging.

The whole thing would be easy for a dispersed nomadic hiking culture to adopt, allowing the management of property and resources to defend the trails and culture of people choosing to live outdoors for the majority of the year.

From Mexico to Implementation

The palm fronds rustle while I consider what the next decade might look like. Ten years of trail research temporarily paused in Mexico, trying to figure out whether accidental democracy can become intentional infrastructure.

The tools exist. The examples work. The need grows more urgent every day as traditional democratic systems fail to address accelerating social challenges.

What we lack isn’t technical capability, it’s collective will to prioritize mutual aid over individual optimization. To treat social media as public utility rather than private entertainment. To believe that real human experience contains more wisdom than algorithmic manipulation.

Building a social media based democracy doesn’t require revolutionary technology. It requires remembering that technology should serve human prosperity rather than corporate extraction.

The prototype could be online within months. The question isn’t whether it’s technically possible, it’s whether enough people will choose collective intelligence over algorithmic addiction.

From a much needed writing retreat that feels like the end of one journey and the beginning of another, the answer depends on who’s ready to walk a different path.

The trail taught me that individual success depends on collective knowledge. Ten years later, I’d love to test that principle at scale. Except there are much smarter people out there, better suited to implementing such an idea, with social networks far more influential than my small group of hiker trash friends… but will they? Will anyone build this idea, or will the next generation give up hope when they had every opportunity to make a meaningful and historic difference?

See also Social Media as Democratic Infrastructure and the fictional short story, The Confessional